Landscape Democracy 2015 Working Group A - Case Study 1

---> back to group page working group A

Airports or Cabbages? Integrating Stakeholders in an Era of Urban Expansion in a Traditional Agrarian Landscape

| Place name | The Filder Plain (Die Filderebene) | |

| Location | Stuttgart | |

| Country | Germany | |

| Author(s) | Schirin Oeding | |

| ||

|

| ||

Rationale

The Filder Plain area of Stuttgart encompasses an area of approximately 22,000 ha south of the city of Stuttgart (Slow Food Deutschland, 2005). Early settlers to the area cultivated the extremely fertile soils of the region, producing intensive crops, primarily vegetables. Today, local farmers joke about the fertility of the soil, saying that no crop rotation is needed, because the soil just keeps on giving. The fine, silty loess, evidence of glacial activity and wind accumulated, is a boon to small vegetable producers in the area (Universität Stuttgart, Geographie). Today, land-use in the Filderplain has shifted dramatically from diversified vegetable production to urban (residential) expansion, including highways, the Stuttgart convention center, and the Stuttgart airport, over the past decades. Currently, farmers can often make more money by selling off land for development than continuing to grow crops. One effect of this change has been on the specialty crop of the Filder Plain, which has been produced since the Middle Ages (Slow Food Deutschland, 2005): a specific variety of tender, pointed cabbage called Filderkraut. Current drops in production are thanks to the changing interests of farmers and the overall shift in land-use focus from growing food to growing the city. Agricultural areas focused on diversified production for human consumption, especially those with extraordinarily rich soils, located in and around growing cities are valuable assets on many levels. Benefits include food security, access, hedonic values, air quality, etc. On the whole, this case study exemplifies the struggle between development and the maintenance of urban or periurban agricultural areas, and asks the question, “How can farmland and built infrastructure, like highways and an airport, co-exist?”

The aim of the case study is to identify some people- and land-centric actions that could be implemented to ensure that a sense of place is fostered and carried forward in this landscape. If such a sense prevails, locals will likely be more involved in decision-making which affects their home landscapes—such as further highway expansions, or housing developments in former apple orchards. The focus of the democratic land-use methods suggested in this case study is to bring communities living in the Möhringen-Fasanenhof area, at the edge of the Filderplains, closer together by providing tangible opportunities to explore their neighbourhoods and foster a connection to each other and to the agricultural roots of the landscape they call home.

Observations

As a way of initially getting to know the "lay of the land" more deeply, I decided to document the intersection of agricultural landscapes and urbanized/periurban landscapes by taking one photograph every day during the first part of this case study. (Not all of them will be posted here.)

Why photographs? There is something contradictory about a landscape that switches from farmland to highway to airport with barely a transition zone in between. In ecological terms, transition zones are vital, dampening the effect that two different landscapes have on each other at their meeting place. My fascination with these zones, ecologically referred to as ecotones, began some time ago, when I was living on the margins of wilderness in northern Vermont. In the spring of 2015, I wrote an article about the subject, in it, I described these ecotones as, "areas of overlap between, for example, forest and meadow. Resplendent margins, ecotones are places where biodiversity not only thrives, it literally builds connectivity between two seemingly disparate environments. Forests taper off into meadows, their shifting identity bridged by shrubs and bushes, then woody plants, a tangle of wildflowers, and eventually, meadow grasses. This identity-shaping botany can be hard to grasp from a scientific perspective: its habitat is loosely defined, and its taxonomy leads us into the trees, or into the meadow, into the light. The movement and growth, or the disappearance, of carefully observed ecotones, can even be an indicator of climate change—think of the aftermath of a receding glacier, for example. The plants that live here are quirky shape-shifters with unclear origins, essential components of life that aren’t easily categorized" (Oeding, 2015). As a farmer, I learned to pay close attention to them, those scrappy settlers of the borderlands. Now, living in an area basically devoid of the wilderness I know from North America, I have begun looking for other areas of interception—where the built landscape meets the bare land, the soil, the hayfield. Taking a picture, for example, of the field where a cover crop blooms in the foreground of an apartment complex raises many questions:

- Why is this field still here?

- Are the days of this fragmented landscape numbered?

- How do the people who live here interact with this landscape?

- How do the farmers feel about farming in such a place?

- How can farmland and built infrastructure best coexist?

I am a great admirer of the Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, whose work documents the race of progress in our landscapes, from China's massive factories to nickel-tailings ponds in Ontario, Canada. His photographs are stunning, shocking, even beautiful. They lay bare painfully beautiful landscapes—and play with our preconceived notions of what beauty looks like. My photographs appear quiet: often the thundering of a highway, or the puttering engine of a tractor, is just out of the shot. I photographed people—adults and children—interacting with their home landscape, as well as instances where no other human was around, a rare event in such a densely settled area. The interaction between quite and noise, between the absence and presence of people, are also key ingredients to understanding the essence of this place. Inspired by Burtynsky, I attempted a variation on his theme: capturing moments in time in a place where progress and tradition are in constant flux and battle.

- Observations

Reflection

What are the major challenges?

-Influx of urban expansion (housing development—often high cost, Stuttgart Airport, Messe, highway expansion)

-Agricultural land sales to developers (loss of prime agricultural land with at least 80-90 "Bodenpunkte"—indicates soil fertility out of total of 120)

-Loss of recreational land-use (agricultural roads used for recreation near the highways are avoided due to noise, unpleasant atmosphere)

-Loss of diverse land-uses (traditional, diversified agricultural uses are lost as developers move in; incl. apple orchards, beekeeping, cattle and small ruminant, diverse vegetable production)

-Loss of place-memories (relatively little signage, for example, informing walkers about the history of the area)

- A Transition from an Urban to Rural Landscape

Options for democratically-based change in Möhringen-Fasanenhof

-Creation of a community garden that is accessible via public transit, bike, and on foot

-Guided Histories with local historians for groups, students, etc., on topics of ecology, memories (involve local seniors), hidden gems, creating unique hand-drawn maps

-Story Walks using maps and signage to add story-telling features to the popular walking routes

-Hub in the Fields as a visible feature for gatherings and information (a focal point in the landscape, something that catches the eye in a relatively flat area)

-Assessing of the status quo of community involvement using Sherry Armstein’s “Ladder of Citizen Participation", creating “Heat maps” to indicate areas of most use/importance to various stakeholder groups (local schoolchildren, elderly, farmers, new arrivals, etc.)

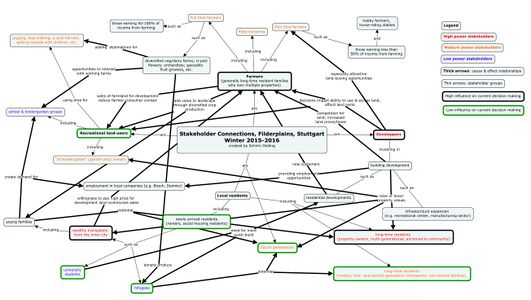

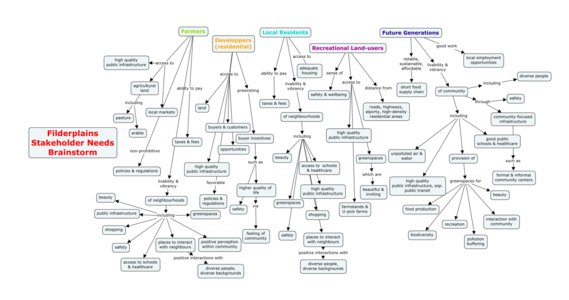

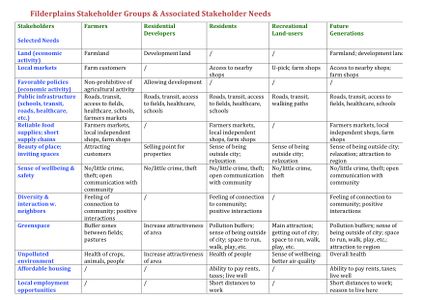

Stakeholder Mapping

- Map of Stakeholder Connections, Filderplains of Stuttgart, Germany

- Brainstorm process for identifying stakeholder needs, Filderplains of Stuttgart, Germany

- Potential Stakeholder Needs Charted, Filderplains of Stuttgart, Germany

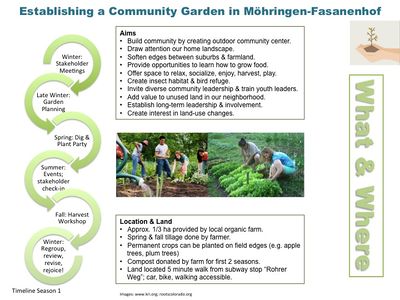

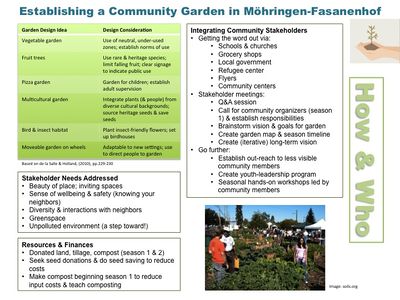

Change Scenario: Establishing a Community Garden in Möhringen-Fasanenhof

"The single greatest lesson the garden teaches is that our relationship to the planet need not be zero-sum, and that as long as the sun still shines and people still can plan and plant, think and do, we can, if we bother to try, find ways to provide for ourselves without diminishing the world." —Michael Pollan, The Omnivore's Dilemma

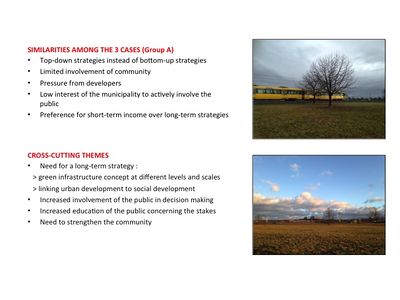

Cross cutting theme

Though all three case studies in our group are located in very different places (Slovakia, Italy, and Germany), we were quickly able to recognize a set of common themes (see slide below). These common themes are likely associated with almost any project where development and community wellness are at odds. The key issues for all the cases are closely linked to both the challenge of future planning and the process of a community gaining a deeper understanding of its common goals and visions—and being empowered to articulate these. In Stuttgart, where my case is located, a current example is the struggle to reduce air pollution caused, primarily, by high-density traffic. Stuttgart is know as the “car city”, since it is home to Mercedes and Porsche, as well as various car parts manufacturers. Clearly, cars are part of the city’s culture. What is more, the industry is a key employer. Nevertheless, the long-term impacts of pollution on people’s health will diminish the quality of life in the city. The struggle here is to provide education and information to communities, motivate the population, and encourage action. Self-determined, informed decision-making may empower community groups not only to implement greening project calling awareness to the importance of green spaces for health and wellbeing, but also lead individuals to reconsider the impacts of their habits and decisions (such as driving to work rather than using public transit). Small changes, such as the establishment of a community garden and its leadership, can lead to larger conversations and, eventually, the potential for positive change.

- Cross-Cutting Themes: Group A

Concluding reflections

While a community garden may not be the solution to end all the problems presented in this case study, it can be a dynamic catalyst for change. During the course of preparing this case study, I have spoken to a diversity of people, read papers (scientific and otherwise), and looked closely at the landscape and how people interact with it. I have generally come to the conclusion that it is sometimes not the enormity of the problem facing a group of people which slows the process, but the reluctance of the stakeholders to get involved. A community garden—a safe, shared space within walking distance of home—can become a keystone in the community, transforming passive passers-by into actively involved members of the community. What is more, the act of gardening is inherently an act of creation: it engenders practical, hands-on problem-solving. A neighborhood faced with the challenges of urban expansion and a growing population needs practical solutions! The garden provides a perfect metaphor for the processes of reconnecting people to place.

References

de la Salle, J. & Holland, M. (2010). Urban Agrarianism: Handbook for Building Sustainable Food & Agriculture Systems in 21st Century Cities. Faringdon, UK: Green Frigate Books.

Oeding, S. (2015). On the Edge of Mystery. Taproot Magazine, Issue 14: WILD, Spring 2015.

Slow Food Deutschland e. V. (n.d.). Filder-Spitzkraut: Arche-Passagier seit Juli 2005. Retrieved from https://www.slowfood.de/biodiversitaet/die_arche_passagiere/filder_spitzkraut/. 11.15.2015

Universität Stuttgart, Geographie. Löss: Entstehung und Verbreitung. Retrieved from http://www.geographie.uni-stuttgart.de/seminare/lehrpfad/Pleistozaen/Loessseite.htm. 11.16.2015

* Do not use images of which you do not hold the copyright.

* Please add internet links to other resources if necessary.

About categories: You can add more categories with this tag: "", add your categories