Lincoln

Planning for expansion: the reinvention of a small town in New Zealand

Rationale: Why is this case study interesting?

This is the story of what shaped and influenced the development of a structure plan for a small town in New Zealand. Lincoln township is intimately linked to the history of Lincoln University. Its historical evolution illustrates many generic aspects of small rural towns in New Zealand, but it has special interest because of the way it is associated with the development of New Zealand. Wide ranging economic and policy reforms and government restructuring has brought about significant changes in the approach to environmental management in New Zealand. The future of Lincoln will be shaped by the goals and principles of the Greater Christchurch Urban Development Strategy, which has identified Lincoln as a growth centre, based upon its potential for a ‘new knowledge economy’. This case study explores the elements, patterns and dynamics that are shaping the character of Lincoln as the community expands and moves from being a sleepy rural township to become a centre of growth and innovation. In particular, I consider the role of Lincoln University in this transition both as a landowner and as an educator actively engaged in local issues and the development of the Landscape Architecture profession in New Zealand.

Author's perspective

As a Landscape Architecture Masters student at Lincoln I approach this case study both from an academic perspective and as a member of the community. My professional background is in regional land use planning and resource management both in northern Canada and China. This has equipped me with a McHargian perspective which we are encouraged to explore further through our design studios in landscape architecture. Experience working with communities has also given me an appreciation of the opportunities and limitations of grass roots initiatives. I believe the case study method provides a systematic and disciplined approach to landscape architecture and exploring Lincoln from this perspective provides a clear insight into the patterns that have shaped the township. As part of the LE:NOTRE Urban Landscapes Seminar this provides a useful resource for learning, collaboration and development of a more culturally aware landscape architecture profession.

Lecture Recording

Paul Wilson's presentation on 10th of December 2008

Landscape and/or urban context

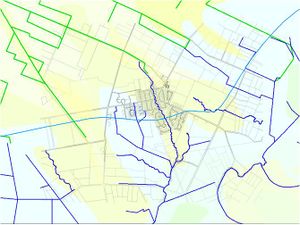

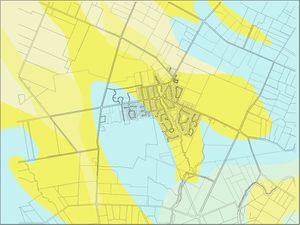

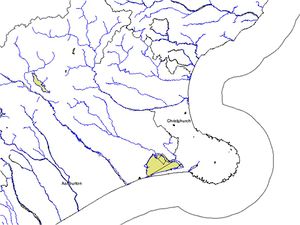

Lincoln is on the Canterbury Plains which extend from Lake Ellesmere (Te Waihora) to the foothills of the Southern Alps. The Lower Plains comprise a broad plain of un-cemented outwash river gravels overlain with variable loess cover from glacial periods [1]. To the north and south mountain-fed rivers extend down to the Pacific Ocean on either side of the distinctive volcanic form of Banks Peninsula. The Waimakariri flood plain extends across the south/eastern edge of Lincoln and here the land is lower. At one time the edge of Lake Ellesmere was close to the centre of the township. This is reflected in the soil types with drier soils found in the north and heavier wetter soils in the south. It is also apparent in the transition between water races and streams, and between springs and wells in the area. The original vegetation also reflected the soil conditions. Management of water is important for draining and irrigating agricultural land. The region has a temperate climate and receives an annual rainfall of 600-800mm/annum with westerly winds predominating in all seasons [2]. Waterways, wetlands and areas of significant remnant vegetation are important for biodiversity and act as corridors for migrating birds. Drainage races extend as far as Lake Ellesmere which is the 5th largest lake in New Zealand and a significant haven for birds. Locally habitat is found around the Liffey Stream system and pockets of vegetation around the University campus and the Crown Research Institutes (CRI's). These provide islands between native remnants.

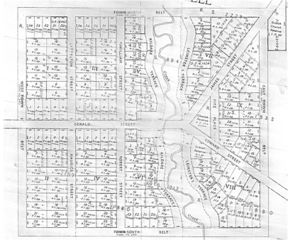

The cultural landscape of the Plains is dominated by agriculture and small settlements. The distant views to the Southern Alps and Port Hills appear between coniferous shelter belts that provide definition to the open landform. The historic layout of Lincoln township is evident in the orderly colonial grid aligned with the main street. There are also a number of heritage buildings and the mature trees along the Liffey stream which help orientate the visitor. No areas or sites of cultural significance to Maori have been identified to date within Lincoln township [3], although Lake Ellesmere to the south has special cultural importance [4]. At the centre of the township along Gerald Street there is a pub and several shops, community services, small commercial establishments and a poorly defined market square. Further along there is a modern café and a line of shops set back from the road facing into a car park. North of the centre there are primary and high schools, elderly residences, a golf course and cemetery. There is also a domain with several sports fields, a bowling club and tennis courts. The cottage garden style plantings and mature vegetation of some of the older sections introduce a distinctively rural European character although native planting now dominate particularly in new areas. There are several new suburban developments each with their own distinctive brand and urban form. Here the lot sizes and street patterns are more irregular than the centre. There are frequent cul-de-sacs, pedestrian ways and many streets are narrower than the older avenues and lined with trees. Some of both the old and new sections have been fenced along the road frontage which detracts from the open street atmosphere.

On the road north-east towards Christchurch, former agricultural land is now dominated by lifestyle blocks which expanded during the 1990’s. Additional planting around these sites reduces the open character and blurs the distinction between urban and rural. In contrast the high rise buildings of Lincoln University emerge above mature trees to the east about one kilometre from the town centre. They are separated from residential areas by productive agricultural land and the Crown Research Institutes. Historic research records for soils in the area make the land invaluable for the region. The campus includes a range of contemporary buildings arranged around Ivey Hall (1878) which dates back to the original School of Agriculture. The campus has grown and adapted to accommodate a growing student population. In the summer the grounds are home of New Zealand Cricket and there are sports fields, amenity gardens, a vineyard and an orchard. Both the University and the town centre are serviced by regular bus services to Hornby and Christchurch. There was once a rail connection to Christchurch and today there are plans to extend a cycle track along the original route.

Cultural/social/political context

- Historical Overview

Today Ngāi Tahu's economic and cultural interests are reflected in the New Zealand landscape and environmental policy. While their influence on the island, its biodiversity and society has come full cicle, the landscape is very different. Many of the patterns of colonial settlement have brought benefits but are irreversible. This is refelected both in the urban form of Lincoln Township and the development of scientific and production agriculture on the plains. The role of the planning system and Landscape Architecture profession in this context is to take a holistic view to manage change in an acceptable way.

Ngāi Tahu The Māori people of the southern islands of New Zealand are known as Ngāi Tahu. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu provides a detailed description of their history [5]. When the first settlers arrived from Polynesia around c.1300 the area was rich in biodiversity. Hunting and clearing of some lowland forest transformed the unoccupied landscape. It also led to the eventual decline of the Giant Moa. During this period the Maori culture developed. Lake Ellesmere gained particular cultural significance. It was known as 'Food Basket of Rakaihautu' a legendary ancestor who helped form the regions landscape. Around 1795 Ngāi Tahu first encountered and traded with Pākehā (European) sealers and whalers. As more migrants arrived they introduced disease and guns which changed their relationship with Europeans and other Maori tribes. In 1840 the Maori signed the Treaty of Waitangi with the British Crown [6]. Since then they were progressively marginalised. In the South Island the Crown purchased millions of acres from Ngāi Tahu on the understanding that areas would be set aside for Maori settlement in the future. This paved the way for a new wave of migrants from Europe. It was only in the late 20th century that efforts were made at reconciliation. These developments have led to a revival in Maori values and culture. In 1991 the Waitangi Tribunal found the tribe to be entitled to substantial redress through a process of negotiated settlements. The Crown's Settlement Offer included cash and mechanisms that “gave Ngāi Tahu the capacity, right and opportunity to re-establish its tribal base” [7]. The Treaty Settlement Area of Lake Ellesmere is in close proximity to Lincoln. The Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Act 1996 established Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu to service the tribe's statutory rights. Their investment company trades under the name Ngāi Tahu Holdings Group and its subsidiaries include Ngāi Tahu Property Limited. The company’s main focus is property investment and development and the management of the Iwi's Right of First Refusal (RFR) to purchase Crown property assets under Part 9 of the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998. Since its inception in 1994 it has grown to become one of the largest property companies in the South Island of New Zealand.

Lincoln Township Settlement of Lincoln Village began in 1863 under the direction of the Canterbury Association which was set up to organise the settlement of the region [8]. It served primarily as an agricultural settlement in an area renowned for its productivity. Christchurch had been established in 1850 based on plans drawn up in London, England prior to departure. By 1875 a rail connection to Lincoln had been established to help transport goods to market. Lincoln has always had a strong community spirit and even as other rural townships have declined it has maintained its vibrancy and retained essential services. In part this is attributed to the presence of the University and Crown Research Institutes, which provide stable employment and investment in the community. The varied demographic does however place demands on the townships accommodation and services. The Lincoln area is also popular for what Cadieux (2008) describes as “amenity migration to urban edge lifestyle landscapes” [9]. During the 1990's urban development was less constrained. Agricultural land between Lincoln and Christchurch became popular for lifestyle blocks. In Lincoln itself new subdivisions were developed, each with a distinctive branding which changed the urban form and rural character of the community. Lincoln became a popular place for professionals and people looking for a place to retire between the country and the city. Today many students commute to Lincoln from more affordable parts of Christchurch. In response to the changing rural character several projects have been initiated by the community including “An Environmental Plan for Lincoln (1974)” and “Lincoln - A vision for our future (2001)” [10], [11] & [12]. The later was intended to provide an integrated approach towards a shared vision for Lincoln and ten visions were identified. Today the grassroots organisations such as Lincoln Envirotown take an active role in community development. This is mirrored accross New Zealand.

Lincoln University The School of Agriculture was established in 1878 reflecting the importance of agriculture for early European settlers and the variety of soil types in the Lincoln area. Lincoln was the first European Agricultural College in the Southern Hemisphere and was instrumental in scientific improvements in the field. The University developed a dairy farm to the southwest of the township in 1952. This was replaced by a new state of the art dairy farm in 2001 on a different site. The College was associated with Canterbury University (formerly Canterbury College) until 1896 and again between 1961 and 1990 during which it was known as Lincoln College. In 1990 it was separated from the University of Canterbury and became a full and self-governing university in its own right, with the title Lincoln University. Today it is one of eight publicly owned and operated government-funded universities that exists and operates under New Zealand statute, principally the New Zealand Education Act 1989. The student population is around 4,500 and there are around 250 staff. It is a research-led institution with an emphasis on land-based disciplines and their associated industries. Responsibility for the University's commercial trading activities is delegated to Lincoln University Holdings Ltd.

Crown Research Institutes (CRI's) In 1926 the Department for Scientific and Industrial Research was established at Lincoln. Unlike its equivalent in the United Kingdom it focused on primary industries, especially agriculture. Developments in wool production and later improvements in dairy hygiene allowed New Zealand to develop its export markets. The country also benefitted from the post WW2 boom and the research facilities grew incrementally through the 1960's, 1970's and 1980's. In 1992 former public resource production functions were devolved to state owned corporations or privatised. CRI's were established under the Crown Research Institutes Act 1992 as Government-owned businesses with a scientific purpose. Each institute is based around a productive sector of the economy or a grouping of natural resources. A number of these are based in Lincoln providing jobs and revenue to the community and links with the University. The CRI’s are positioned to provide technological and information based services and Lincoln has the potential to develop a 'new knowledge economy'. This was identified under the GCUDS. The CRI's are also major landowners in Lincoln although much of this is dedicated to longterm research trials.

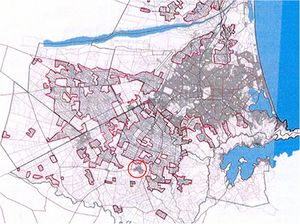

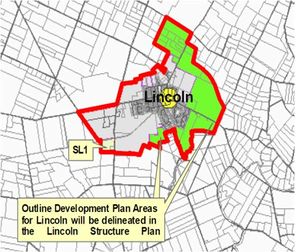

Planning System As a colony New Zealand inherited a government and planning system similar to the United Kingdom. The flow of trade and migrants from the west helped maintain this heritage until the 1980’s when pressures from globalisation led New Zealand to deregulate and restructure its economy. Resource production and environmental management functions were separated and agricultural subsidies removed. A new institutional framework was delivered through the Environment Act 1986, the Conservation Act 1987 and amendments to the Local Government Act 1974 in 1989. This laid a foundation for the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA91) and Local Government Act 2002 (LGA02), which provide the legislative context in which the Lincoln Structure Plan (LSP) was developed. The RMA91 superseded a multitude of other statutes with a philosophy of 'sustainable management' and created a three tier hierarchical planning framework. Central Government retains an overview function while environmental monitoring and management responsibilities are devolved to elected Regional (Environment Canterbury) and District Councils (Selwyn District Council). Under RMA91 National Policy Statements and Regional Policy Statements (RPS) are prepared and each District is required to prepare a District Plan. This is a three tiered approach where all documents must be consistent with RMA91 and each other. The new legislative framework presented a challenge to local government resources and conventional planning processes. The familiar zoning approach was replaced by effects based management with decisions based on 'perceived sustainability'. It took time to develop and approve the District Plans and it was difficult to attend to all community concerns, particularly in respect to the tensions over development on the urban fringe. This was apparent in the withdrawal of the Proposed Selwyn District Plan in 1998 due to the large number of submissions. The LGA02 introduced a new framework under which local authorities would operate. The Councils role changed from simply providing physical infrastructure to promoting community well-being. The LGA02 requires all local authorities to prepare 'community outcomes' and develop a Long Term Council Community Plan (LTCCP). There is also an obligation to prepare asset management plan and manage council assets and services more like a business. An integrated landscape management approach is also encouraged as a means to achieve sustainability. Around 87% of the New Zealand population live in towns and cities [13]. It soon became apparent that to achieve 'community outcomes' under the LGA02 would require greater attention to urban design. In subsequent years a series of consensus building initiatives were developed to address requirements under LGA02 and RMA91 under the three tiers of government. The National 'Urban Design Protocol'(UDP) provides a "framework of national policy guidance around successful towns and cities and quality urban design" [14]. At the Regional Level the Greater Christchurch Urban Development Strategy (GCUDS) was initiated. This sets out land use distribution, particularly the areas available for urban development, the household densities for various areas and other key components for consolidated and integrated urban development and that land which is to remain rural for resource protection and enhancement and other reasons [15]. The intention is that the GCUDS will be adopted as a new chapter in the RPS under the RMA91. The GCUDS projected that the population of Selwyn District where Lincoln is located would grow by 134% by 2041. This GCUDS provided a basis for developing the Lincoln Structure Plan (LSP). The purpose of the LSP is to outline an urban design vision for the future development of Lincoln Township and to provide a strategic framework to guide the development process [3]. This will provide a basis for changes to the Selwyn District Plan.

Landscape Architecture Profession Jones (2000) provides a detailed history of the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects and additional information is provided in Wilson (2005)[16], [17]. The foundation of the profession in New Zealand is closely related to the University of Lincoln. Professional education in landscape architecture was first offered at Lincoln in 1969 and by 1972 there were sufficient graduates to form the institute. The majority of landscape architects practicing in New Zealand today have spent time at Lincoln University. In 2009 the University celebrates 40 years of landscape architecture education and a new landscape building is under construction. Under the RMA91 landscape is seen as an "integrator, embracing other resources" (Henderson & de Lambert 1993) [18]. This has provided impetus for growth of the profession in the past two decades. Being involved in Structure Planning is one of a broad range of tasks a landscape architect may be called upon to undertake in New Zealand today.

History

Spatial analysis of area/project/plan

What are the main structural characteristics?

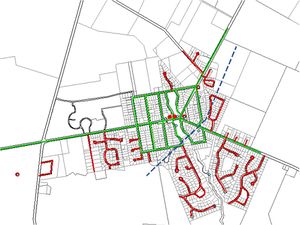

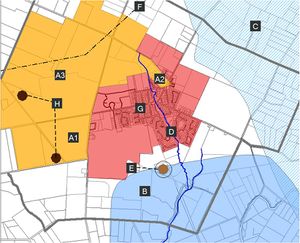

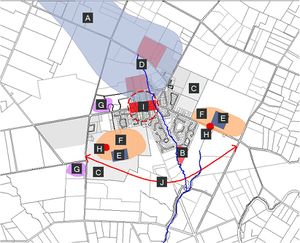

- An important part of the LSP process was to identify and map the main structural features or the 'opportunities and constraints' in Lincoln.

| CONSTRAINTS | OPPORTUNITIES | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

How has it been shaped?

- Under RMA91 agricultural land between development and conservation has become highly contested.

- The growth of Lincoln University and the CRI’s is attracting investment and jobs to Lincoln.

- The GCUDS identified Lincoln as a regional growth centre based on its potential for a ‘new knowledge economy’ providing a regional framework for Structure Plan development.

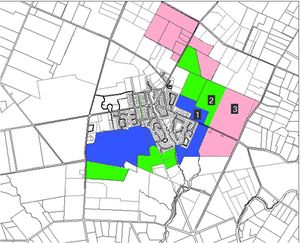

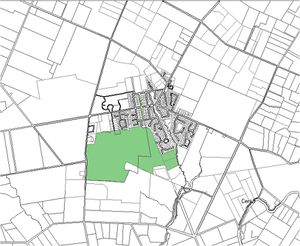

- The University and CRI’s recognized the financial opportunities of residential and commercial land development. They also value the independence provided by their rural setting. Some land is invaluable because of historic research trial records. The Universities old dairy block represents an opportunity for residential development.

- Ngāi Tahu Property Limited has the Right of First Refusal (RFR) on the sale of Crown Land (including Lincoln University and CRI’s lands) under the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998.

- The old dairy block has relatively low drainage capacity and a comprehensive stormwater system is required.

- The existing sewage treatment system has limited capacity and is in close proximity to proposed residential areas. Sewage treatment is a growth issue that is being addressed regionally.

- The community was actively interested in their future. Community initiatives sought the expertise of the University and support of Selwyn District Council (SDC) prior to LSP. These provided a foundation for structure planning process and helped mobilized the community.

Were there any critical decisions?

- Partner Councils of the GCUDS decided an integrated approach was required to manage growth in the region.

- The GCUDS was initiated, population growth projections were made and four options for future development patterns were presented to the public. Public preference was for a more concentrated pattern of development including a focus on well-defined urban centres. Ultimately the GCUDS partners decided to include some greenfield development to provide room for the market to adapt to the new level of intensification.

- GCUDS Inquiry-by-design workshops identified Lincoln as a 'growth node' based on the University, CRI's and the potential for employment and a 'new economy' to develop.

- SDC decided to adopt land based treatment and disposal of sewerage effluent as its preferred policy to cater for the growth anticipated in the GCUDS.

- Some tensions arose over the role of major landowner (including the University and CRI's) in the planning process.

- SDC decided to initiate the LSP process and engage the community including the major landowners.

- Lincoln University and Ngāi Tahu Property Limited decided to undertake a joint venture to develop the old dairy farm site for residential development.

- Community initiatives led by Lincoln Envirotown decided to engage University and CRI's expertise.

- SDC decided to develop the Integrated Stormwater Management Plan (ISMP) in parallel with the LSP. Participants agreed on the importance of blue and green networks in managing stormwater, biodiversity and aesthetics in new residential areas.

- SDC chose to revise the GCUDS growth projections during the LSP process and lodged a submission to this effect in proposed Change 1 to the RPS.

Core Questions Working Group Green Structure Planning

How does funding influence the planning and use of public space?

- There is a strong legislative basis for public involvement in decision making in New Zealand. This is reflected both in funding, planning, use and management of public space. The council’s role is one of service provision and public space is regarded as a community asset. Dedicating resources to Structure Planning helps build consensus and a shared sense of ownership. This is turn helps the council achieve the 'community outcomes' it is committed to under the LGA02. Additional funding is also provided in support of specific community initiatives such as 'Environment Canterbury Environmental Enhancement Fund'. Such initiatives help reduce the burden on councils to develop and maintain open space. It also mobilizes people to value and utilise the space around them.

How are spaces within the site used both currently and projected?

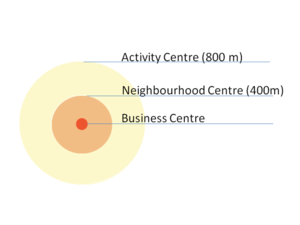

- At the broad scale agricultural land currently separates residential areas of Lincoln from the University campus. Proposals for residential development and a business park on the old dairy farm site will draw these spaces together. Additional activity centres will develop and movement will no longer be restricted to the main road. A bye-pass may be required and new access points to the south of the township. Improved definition of the town centre and market square is also necessary to provide a gathering place for the community. The historic buildings could contribute to this area. Integrating green space with cycle and pedestrian movement networks also features strongly in the vision for Lincoln. Open space will also be necessary to make higher density living appealing and achieve an average density of 10.7 HH/ha. Areas for residential development will be released in stages relative to expansion to encourage an appropriate mix and density of development.

How can the historic elements / layers be integrated?

- Historic elements of Lincoln fall into two main categories. (A) Pre-European elements include native vegetation which contributes to a sense of place and local ecology, this can be integrated in design through local plant signatures; Maori cultural values can provide a foundation for decision making, their role as stewards of the land is also effectively formalised in legislation. (B) Colonial historic elements are reflected in the highly modified agricultural landscape, the formal grid of the original settlement and historic buildings in the township and University Campus. Containing development within Lincoln’s urban limits will help maintain the agricultural landscape for which the Canterbury Plains is known. Historic buildings have also been preserved and could be used to better define the centre of the township. The original railway network can be re-developed into a cycle path.

How do the contributing elements of water relate to the project?

- Recreation: The Liffey Stream introduces variation in the topography and layout of the township. It is also a popular place for passive recreation although there appear some tension between private gardens backing on to the water and public access. Irrigation also maintains the aesthetics of recreational turf areas. Blue and green networks feature as a means of managing storm water and maintaining aesthetics. The old dairy farm site has a relatively low drainage capacity and wetlands will be required to address storm water runoff.

- Historic: the Canterbury Plains were formed by glacial river’s which is reflected in the soil conditions, native vegetation and the drainage characteristics of the area. These in turn influenced the choice of site, its expansion and the urban form that developed.

- Transportation: There are several bridges linking from one side of the township to the other. These are important given that the Liffey intersects the community.

- Environment: Water is a key component of Lincoln and this is reflected in the ISMP, which was developed in parallel with the Structure Plan. Water provides a haven for biodiversity and helps filter pollutants from the water before it reaches the Liffey Stream. Lake Ellesmere and other local water bodies are influenced by agricultural run off and water extraction.

How does the built environment relate to the landscape around it?

- The Canterbury Plains is dominated by agriculture and townships such as Lincoln. The underlying landform offers little topographic relief. Expansion of lifestyle blocks in the 1990’s introduced both additional built form into the open landscape and additional vegetation. The Structure Plan establishes boundaries to help manage growth and the traditional relationship between the built environment and the surrounding landscape. As residential density increases green space becomes more important to maintain the quality of the environment. It may be possible to leverage higher density living off green space and views to the distant mountains. The Universities has several multi-storey buildings which are an anomaly in the Plain landscape. Today they are screened somewhat by large trees. The original concept behind the “Hilgendorf Wing” design was that the landscape would flow underneath. Unfortunately the ground floor was bricked up soon after being completed to provide additional office space! Recreational areas and green space may help soften the transition between the built environment and the surrounding landscape. If people value these areas it will help contain development.

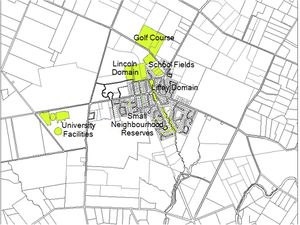

What functions should open space perform to help achieve the established goals?

- Open space in Lincoln township performs several functions from managing stormwater (blue network), providing habitat (green network), an aesthetically pleasing place for recreation (social network) and linking key features (movement network). It also provides a transition between different land uses. These in turn help contribute to the community outcomes (goals for which the council is accountable).

How cultural factors (environmental perceptions, social conditions, ecological literacy, etc…) can affect the design process and its post implementation performance?

- There is some evidence to suggest that public preference for productive or natural landscapes depends on cultural origins. This is relevant to Lincoln which has a varied demographic and many international students. Similar questions arise regarding the perceived naturalness of the Canterbury Plains landscape. Facilitators and expertise in areas such as hydrology and landscape ecology can help clarify perceptions, dispel myths about the environment and explore resistance to change. The vision of the LSP is development that is complementary to the township. This may require changes to longstanding circulation patterns and a reduction in car use. The LSP process was useful in that it brought together the different stakeholders to explore these kinds of issues which helped break down cultural barriers and examine the tensions that exist. This can help to ensure the project is implemented effectively.

Analysis of program/function

What are the main functional characteristics?

- The purpose of the Lincoln Structure Plan (LSP) is to outline an urban design vision for the future development of Lincoln Township and to provide a strategic framework to guide the development process. The LSP has been prepared in order to facilitate an integrated approach to achieving the sustainable management of the natural and physical resources of the Lincoln Study Area. This includes:

- Development of an urban design strategy for the area;

- Identification of key natural resources and community assets within and related to the area;

- Establishing an integrated land use pattern that responds to the characteristics of the area;

- Identification of infrastructure requirements to facilitate urban development.

How have they been expressed or incorporated?

Blue Network

- Implementation: Obtain resource consents to implement ISMP; aquire land for wetland system; implement regional sewerage system; detail design of wastewater and stormwater system; and controls on impervious areas

Green Network

- Implementation: Determine land required for future recreational needs; secure funding; investigate co-location opportunities; plan main street enhancement including street trees; create green linkages between areas of activity; create parks and reserves within 10 minutes walk from all residences; enhance Liffey corridor; explore potential expansion of golf course to buffer residential from research activities.

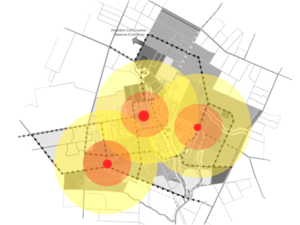

The use of Native plants has become increasingly popular in New Zealand. This is supported in the Canterbury region by Motukarara Conservation Nursery run by the Department of Conservation, who supply native plants specific to a particular area (i.e. Canterbury Plains Native Plants). The University and CRI's have been instrumental in developing Low Impact Urban Design and Development (LIUDD) Principles, with a Biodiversity Focus. Additional research has been done to determine the required patch size and distribution to create a systems of ‘stepping stones’ and green corridors to encourage native birds back to urban areas and help regenerate remnant bush. Recent publications include:

Movement Network

- Implementation: Ensure connectivity of roading, pedestrian and cycle network (especially with University); establish alignment for new roads, entrances and connections; establish bridge link across Liffey; investigate park and ride feasibility and shuttle bus; facilitate continuation of rail trail; promote new bus route via Halswell; integrate bus and cycle lanes in existing street where possible; provide for bus shelters; ensure adequte town centre parking.

Social Network

- Implementation: Develop new community centre, council service centre and libary; investigate options for affordable housing and redevelopment of old Country Club site; plan for new schools and co-use of facilities; establish ongoing liason group within Lincoln.

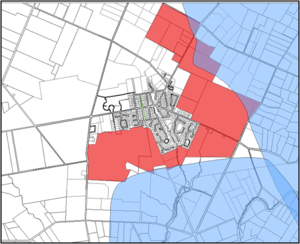

Land Use

- Implementation: Review and revise District Plan growth of township policy; develop living zone and lot size standards and rules; develop a recreation and open space zone; prepare an outline plan for expansion of urban area based on LSP; rezone to allow for new supermarket in towncentre; rezone land for residential areas; develop a new business park zone; investigate low impact urban design solutions for possible inclusion in District Plan.

Analysis of design/planning process

How was the area/project/plan formulated and implemented?

- The LSP was formulated through a generic structure planning process. The Ministry of the Environment Quality Planning and Urban Design Toolkit websites provide best practice examples of structure planning and other tools.

| GENERIC ASPECTS OF PROCESS | LINCOLN PROCESS ELEMENTS |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Were there any important consultations?

- The Urban Design Protocol, Greater Christchurch Urban Development Strategy and the Lincoln Structure Plan were all designed to be collaborative processes. This reflected the new 'community outcomes' provision enacted under the LGA02 who's intent was "to enable a strategic planning approach with an emphasis on greater collaboration/co-operation between central government and local government, between the public, private and voluntary/community sectors, and with Iwi" [19]. The Lincoln Structure Plan (Page 10) includes details of consultations undertaken in its preparation. Participants in the LSP process included:

| AREA | GROUP |

|---|---|

| Environment | Environment Canterbury, Department of Conservation, Lincoln Envirotown Trust, L2 Drainage Committee, Waihora Ellesmere Trust; |

| Land Owners | Developers and landowners known to want to develop their land, including Lincoln University, SDC Corporate Manager (Selwyn District Council), Ngāi Tahu Property (Ngāi Tahu) |

| Education and Research | Crown Research Institutes (Ag Research, Crop & Food Research, Landcare Research), Lincoln University, Lincoln University Students Association |

| Local Business | Lincoln Business Association, SDC Economic Development Officer (Selwyn District Council), Federated Farmers; |

| Community and Services | Public, Lincoln Community Committee, Lincoln High School, Lincoln Primary School, Lincoln Domain Management Committee, Lincoln and Districts Community, Care Association, Ministry of Education, SDC Lincoln Library |

Were there any important collaborations?

- Selwyn District Council collaborated with major landowners. It was evident from the tensions that arose in the GCUDS process that major landowners and developers would need to contribute to a workable plan for the township. Additional meetings were arranged with Ngāi Tahu, the University, Landcare Research and Crop and Food Research to discuss the 'Issues and Options Report' with the project team.

- The University and CRI's collaborated with the Community through research, teaching and community initatives to and contributed to a visions for the future of the township.

- University and Ngāi Tahu agreed on a joint venture to develop the old dairy farm in the area.

Analysis of use/users

How is the area/project/plan used and by whom?

- The LSP creates a framework to guide development and will be used as a basis for:

- Future changes to the District Plan;

- Developing an infrastructure programme;

- Determining the Long Term Council Community Plan.

- Once approved they will contribute to decision making on development projects in the Lincoln area. Lincoln's population is projected to grow from 2,720 people (938 households) to 11,310 people (3,900 households) by 2041 (3). As people, businesses, employment and investment is attracted to the region the framework provided by the LSP will contribute to:

| USER | HOW WILL THE PLAN BE USED? |

|---|---|

| Environment Canterbury | projections may be adopted through the GCUDS in Change No.1 to the Regional Policy Statement. |

| Metro Bus Service | to inform routing, service frequency and infrastructure requirements. |

| Employer Groups | to help planning and supporting local employment initiatives. |

| Investors | to help investors and local Business Associations to identify business opportunities. |

| Ministry of Education | to forcast school places, new developments. |

| Selwyn District Council | to help plan the Council work programme including infrastructure and community outcomes. |

| Developers and Real Estate | to assess real estate market outlook and identify appropriate standards for future development. |

| Potential Residents | to decide if Lincoln will meet their aspirations both today and in the future. |

Is the use changing? Are there any issues?

- A new retail area has developed a short distance from the town centre. Parking is arranged on the road frontage which detracts from the vibrancy of the main street.

- In 2008 new subdivisions continue to be developed at relatively low densities. It is yet to be determined how the market will respond to higher density housing and whether it can be encouraged within the existing legislative framework.

- A supermarket has been proposed in an area zoned for a business park. There is an underlying tension between existing business owners who fear it may draw trade away from the town centre and urban designers who see an opportunity for growth and links with the University campus and CRI's. Another consideration is that a large supermarket would detract from the character of the existing town centre.

- A supermarket location can have a major influence on the future development of the township. Similarly questions remain as to where to locate community services and ciculation routes.

- Infrastructure needed to convey wastewater to a centralised sewage treatment facility operating at The Pines (Rolleston) is extremely important as the capacity limitations of the existing situation will constrain growth.

- As the population grows those people who contributed to the LSP will become the minority. Both the Community Outcomes and the LSP may need to be revisited to accomodate new interests. Similarly new residents and businesses will need to be informed about the Structure Plan.

- Questions remain as to how best to develop linkages between the Township and University. For example is it possible to reorientate the campus by developing a southern byepass and bus route along the east side of the campus or will increased traffic create a strong barrier.

- It is not clear what impact the 'glabal economic downturn' will have on the development of Lincolns. New Zealand is heaviliy dependent on agricultural exports and changes in the market are reflected in the role of CRI's in Lincoln Township. For example recent changes in the global wool market have led to redundancies among the CRI's. Similarly global exchange rates also influence the number of foreign students enroled at the Universiy.

- Beyond the urban limits there is a intensification of dairy farming and irrigation which has impacts on the ground water and the landscape of the plains.

- GCUDS projections provided a basis for the draft LSP Issues and Options Report. Subesequently, SDC lodged a submission on Change 1 with respect to the UDS projections and the final LSP is based on this submission. Proposed Change 1 to the RPS was notified on 28 July 2007. Its purpose is to implement the GCUDS. It may be necessary to revisit the LSP following the release of decisions on Change 1 and resolution of any subsequent appeals to the Environment Court.

Future development directions

How is the area/project/plan evolving?

- On Wednesday 28 May 2008, the Council adopted the Lincoln Structure Plan and Integrated Stormwater Management Plan and agreed to accommodate this in the District Plan by:

- amending Section 4 Growth of Townships (affecting the whole of the district);

- amending the policy framework specific to Lincoln; and

- adding provisions for outline development plans, new zones and staging of development.

- These plan changes will be developed and notified by the end of 2008 (Details of plan changes).

- It is difficult to attribute changes in Lincoln Township directly to the LSP at this early stage. In many cases their conception may pre-date the process. Nevertheless, many developments are consistent with the broad aims of the LSP. This appears to reflect the consensus developed in previous initiatives which were subsequently considered in the LSP process.

Are there any future goals?

- The LSP is a 'package'. It should be a priority to work towards the implementation goals consistently to maintain the integrity of the overall structure.

- The LSP goal for overall density is 10.7 households per hectare.

- Councils are required to revise the community outcomes every 6 years and this will require a review of the structure plan.

Peer reviews or critique

Has the area/ project/plan been reviewed by academic or professional reviewers?

- The LSP was developed through a participatory process which involved critical review by the public and experts. For example inquiry-by-design workshops and focus group meetings were held to consider the different options.

- The LSP was subject to further review by the Council prior to adoption on Wednesday 28 May 2008.

- Environmental planning in New Zealand is not a static process, nor is it restricted to a particular area. Structure Planning is part of the Urban Design Toolkit that contributes to various issues. Subsequent review of the LSP will occur as follows:

- By Council experts in developing changes to the District Plan.

- Under the GCUDS and Change 1 to the RPS the projections and staging pattern will be reviewed.

- As part of an environmental court hearings on resource consent applications or submissions relating to plan revisions.

- In review of 'community outcomes' and progress to achieving them (every 6 years) the LSP will be revisited.

- Academic review of the LSP through design studios and research by the University.

What were their main evaluations?

- At this stage it is clear that the LSP process and broader policy framework has helped mobilise the community and build consensus. However, the LSP is a long term plan it will take some time before a valid evaluation can be made.

Points of success and limitations

What do you see as the main points of success and limitations of the area/project/plan?

| SUCCESSES | LIMITATIONS |

|---|---|

|

|

What can be generalized from this case study?

Are there any important theoretical insights?

- There are tensions between the environmental bottom line approach of the RMA91 and the need for land use and structure plans in the LGA02.

- Economics cannot be separated from environmental effects. Policy must address both.

- Structure Planning is a holistic approach that deals with the complexity of urban development and intensification. Landscape architects are equiped with the skills necessary to facilitate this process.

- Mapping opportunities and constraints allows people to see what is possible and make informed decisions.

- It is essential to involve major landowners in planning to ensure the resulting plans and policies are workable.

- Clear zoning boundaries are required to contain development. Staging release of land may encourage appropriate residential density to develop.

- The UDP, GCUDS and LSP has made contributed to standardise best practice in urban design and address areas which are not explicit in the RMA91.

- Participatory processes may encourage collaboration and partnerships which might not otherwise be considered.

- The NZ approach to 'sustainable development' and decision making under the RMA91 and LGA02 provides room for reconciliation and the adoption of Maori values in New Zealand society as a whole. But it also leads to progressive institutionalisation of Maori values as new precidents are created. It is therefore important that Maori views are representative of the community and not simply economic interests.

- Existing urban, land use (i.e. research) and ownership has a major impact on subsequent developments.

- A holistic approach to planning requires a holistic approach to implementation.

Which research questions does it generate?

- 1) What character and identity should be promoted as rural townships become part of the urban network?

- 2) How do you make high density living attractive in a semi rural setting?

- 3) How do you balance Ngāi Tahu cultural values with aspirations for economic development? [20].

- 4) How do you balance the need for 'expertise' with the interests of Ngāi Tahu and public in decision making?

- 5) How do you design the interface between a University and Township?

- 6) How do you accomodate the infrastructure of growth while protecting existing urban form, business and community interests?

- 7) How do you balance a long term approach to planning with the interests of new residents in a growing township?

Student Projects

LASC 320 Sustainable Landscape Design

References

- ↑ Canterbury Regional Council. (1993). Canterbury Regional Landscape Study (Volume 1 and 2). Prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited and Lucas Associates. Christchurch, New Zealand.

- ↑ Bennett, E., Clayton, A., Roper-Lindsay, J., Wilson, A., Fussell, A. & Johnson, C. (1993). Natural Resources of the Canterbury Region: A Survey and Evaluation for Management. Christchurch, New Zealand: Ministry of Works and Development, Environmental Design Section

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Selwyn District Council (2008). Lincoln Structure Plan. Christchurch, New Zealand: Selwyn District Council. Retrieved from: http://www.selwyn.govt.nz/planning/Lincoln/final.pdf

- ↑ Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. (2005). Te Waihora Joint Management Plan. Christchurch, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. Retrieved from: http://www.doc.govt.nz/publications/about-doc/role/policies-and-plans/te-waihora-joint-management-plan/

- ↑ Who We Are. (2008, November 25). Retrieved from Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Web site: http://www.ngaitahu.iwi.nz/About%20Ngai%20Tahu/Who%20We%20Are

- ↑ Ministry of Culture and Heritage. (2007, November 21). Read the Treaty. Retrieved from http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/politics/treaty/read-the-treaty/english-text

- ↑ Economic Security. (2008, November 25). Retrieved from Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Web site: http://www.ngaitahu.iwi.nz/About%20Ngai%20Tahu/Who%20We%20Are

- ↑ Lincoln University Profile (2008, November 25th) Retrieved from the University of Lincoln Web site: http://www.lincoln.ac.nz/section69.html?

- ↑ Cadieux, K. V. (2008). Political ecology of exurban ‘‘lifestyle’’ landscapes at Christchurch’s contested urban fence. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 7 (2008) 183–194. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2008.05.003 Retrieved from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B7GJD-4SX3HSK-2&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=e04ebbaa7f1931582edcd52e993e7335

- ↑ Jackman, A. E., Mason, S. M., and Densem, G. H. (1974). An Environmental Plan for Lincoln Village – prepared for the Environment Committee of Lincoln, Landscape Consulting Services, Landscape Architecture Section, Horticulture Department, Lincoln College

- ↑ Bowring, J., Montgomery, R., Rixecker, S., Kissling, C. and Steven. A. (2001). Lincoln: a vision for our future : a community-participation based envisioning project for the future Lincoln village. Volume II. Background Data. A joint Selwyn District Council and University of Lincoln Project

- ↑ Bowring, J., Montgomery, R., Rixecker, S., Kissling, C. and Steven. A. 2001. Lincoln: a vision for our future : a community-participation based envisioning project for the future Lincoln village. Volume I. Report. A joint Selwyn District Council and University of Lincoln Project

- ↑ (13) Department of Internal Affairs (2008). Building Sustainable Urban Communities. Discussion Document. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved from: http://www.dia.govt.nz/diawebsite.nsf/Files/BSUCwholedocument/$file/BSUCwholedocument.pdf

- ↑ Ministry of the Environment. (2005). New Zealand Urban Design Protocol. Retrieved from: http://www.mfe.govt.nz/publications/urban/design-protocol-mar05/urban-design-protocol-colour.pdf

- ↑ Urban Development Strategy. (2007). Greater Christchurch Urban Development Strategy and Action Plan 2007. Retrieved from: www.greaterchristchurch.org.nz/StrategyDocument/UDSActionPlan2007.pdf

- ↑ Jones, M (2000). History of the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects. Retrieved from: http://www.nzila.co.nz/conf_coming.asp

- ↑ Dr Wilson, J. (2005). Christchurch City Contextual History Overview Full. Retrieved from: http://www.ccc.govt.nz/Christchurch/Heritage/Publications/ChristchurchCityContextualHistoryOverview/ChristchurchCityContextualHistoryOverviewFull.pdf

- ↑ Henderson, E. & de Lambert, R. (1993). Landscape Values and Resource Management. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry for the Environment

- ↑ Local Government New Zealand. 2004. Realising the Potential of the Community Outcome Process. Prepared by McKinlay Douglas Limited. Retrieved from: http://www.lgnz.co.nz/library/publications/Realising_the_Potential.pdf

- ↑ Sautet, F. (2008). Once were iwi? : a brief institutional analysis of Māori tribal organisations through time, Working Paper 3. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Business Roundtable. Retrieved from: http://www.nzbr.org.nz/documents/publications/Once%20Were%20Iwi.pdf

About categories: You can add more categories by copying the tag and filling in your additional categories