Group O - Collaborative Climate Adaption Project: Difference between revisions

| Line 483: | Line 483: | ||

(10) Munich Statistical Office (Statistisches Amt der Landeshauptstadt München) | (10) Munich Statistical Office (Statistisches Amt der Landeshauptstadt München) | ||

(11) | (11) Solare Nahwärme und Langezeit-Wärmespeicher (Forschungbericht zum BMU Vorhaben 0329607L. Solites) | ||

(12) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munich | (12) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munich | ||

(13) | (13) CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE ALPS. Facts - Impacts - Adaptation (Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety) | ||

http://www.zaharias.net/wb-ackwohn.php?lg=en | http://www.zaharias.net/wb-ackwohn.php?lg=en | ||

Revision as of 03:28, 14 January 2013

| Area | Munich | |

| Place | Ackermannbogen | |

| Country | Germany | |

| Topic | renewable energy application | |

| Author(s) | Cenke Jiang, Andreea Pascu, Le Trang Nguyen | |

| ||

|

| ||

Rationale: Why have you selected this case study area?

- Munich is the capital city of Bavaria, one of Germany's three largest cities with the population of 1.42 million people and has the strongest economy of the whole country. This is a globally cosmopolitan city and also has the leading renewable energy policy.

- Ackermannbogen is a district of Munich particularly planned to be one of the front-runners of solar district heating. This is a part of the city's aim: 100% renewable energy for Munich in 2015. This area is a perfect practical example of building a green energy system and an innovative concept of integrating solar heating machines with green space.

- The scale of the area is large enough to reflect the changing of climate upon it, but not too immense to propose detailed and practical solutions. Also although our seminar platform is international, at least two of us can approach the site in Germany and German resources; the result of our research can be then directly re-confirmed and feedbacked by a large group of German participants.

Authors' perspectives

- One interesting feature of urban development history of Germany are the areas called "Conversion areas". Since the beginning of 1990s the troops of Germany’s Federal Armed Forces had been significantly reduced, that consequently led to the free land use from military in many German cities. The conversion started from the high urban needs, then soon realized its ecological potential. Many areas were converted into residential or public areas in the sense of climate changing awareness and became living model area (e.g: Vauban in Freiburg, Halles in Saale, Patrick-Henry village in Heidelberg...etc). Ackermannbogen is maybe one of the most well-known and well-done conversions due to its scale and perspective, and still in "adapting" progress. In our opinion, this type of conversion is the right attitude and action connecting history-presence-future of an area.

- We all come from different backgrounds (architecture and landscape architecture), but our aspirations meet where the climate is actually changing and we believe renewable energy and mitigation is the key solution for the future. We chose Ackermannbogen as a project-case study, more than a reality-case study, because it is a great project which was designed and currently being built and continually adjusted for the future. Our aim is to learn from such massive plan and to make our own proposals in the context of pre-designed but considering the factor of climate changing.

Urban context

In the late eighties, the city of Munich laid the foundation stone for a municipal policy committed to promoting renewable sources of energy by emphasising energy saving. As early as 1991, the Munich municipal council decided to concentrate on lowering CO2 emissions by 30% in 2005 and by 50% in 2010. So far, the City of Munich's climate protection policy has respected Kyoto protocol objectives even though this was not the case before they were defined.

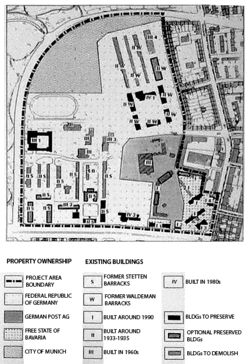

Ackermannbogen district, or the former Waldmann Stetten barracks was planned at that time. In a very attractive location next to the Olympic Park and adjacent to Schwabing area, it offers the ability to resolve arisen urban deficiency and to make an important contribution for housing in Munich. In May 1992, the first step toward redevelopment of the site was already done. The city of Munich took the "decision to initiate urban development action on the area of the Waldmann Stetten barracks". This was followed in June 1994, a structure plan for the area of the barracks was made and a year later the consequent establishment of a comprehensive site report, created by the architects Dragomirand landscape architects Stahr + Haberland. As part of this opinion, urban and landscape planning conditions and the state of civil structures were investigated and evaluated.

In February 1995, the decision of the Ministerial Council of the Free State of Bavaria followed, the Waldmann-Stetten barracks was carried on in the program "Bavarian Future, settlement models - new ways to economical, ecological and social housing in Germany". Based on these foundations, in July 1996, the City Planning Department in Munich announced an urban design and landscape design idea competition for building and landscape architects.

In 1998, the architect Christian Vogel and landscape architect Rita Lex Kerfers won the first prize. The central design idea of the community planning was to create a wide range of different housing types - from double or terraced houses to apartment buildings. In the same year, for the development of the area planning, the city of Munich set all properties on the site for sale and appropriately restricted to private investor purchase.

Overall character

The project area is located in the northern part of the Neuhausen-Oberwiesenfeld district in the north of Munich, close to the southern edge of the Olympic site and connects directly to the Schwabing district. It is bounded by the Ackermann Road to the west, the Deidesheimer to the north, Saar and Winzererstraße the east and Schwere–Reichter Road in the south.

To the south from the Schwere–Reichter Road, there is another smaller and still-in-used barracks (Luitpold barracks); another small, self-contained residential subdivision and several gas stations. Extended from this area are official buildings and public facilities (located on Infantry Road, Hess Road, Loth Road and Dachauer Road).

In the east side of the project area is the Schwabing-West district with a dense block-buliding structure. Further to the north, the Middle Ring, Frankfurter Ring create a business and industrial belt, making an urban barrier from the available landscape freedom.

This area is not far from surrounding significant areas, easily reached by trains, buses and tram system:

- approx. 3km from the City centre

- approx. 2km from München Freiheit

- approx. 1,5km from Luitpold Park

- approx. 3km from English Garden

This convenient location therefore requires an attractive planning for both residents and visitors, which is quite challenging due to the expected high-used pressure.

Land use

The range of the Waldmann Stetten barracks' development planning covers an area of 39.5 hectares, of which the ownership approx. is distributed:

- 16.4 hectares as former Stetten barracks, owned by the Federal Republic of Germany

- 5.6 hectares owned by the city of Munich

- 4.5 hectares belong to Deutsche Post AG

- 2.3 ha the state of Bavaria (1)

- 1 ha of the Students'adminstration (Studentwerk)

- the rest belongs to settlement owners

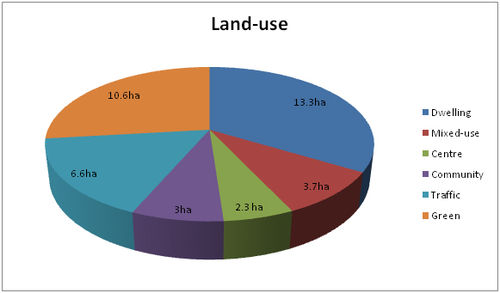

The area's land-use was planned:

- 13,3 ha generally for residential area with approx. 2,200 dwellings

- 3,7 ha mixed-use area with aprrox. 1000 jobs

- 2,3 ha central area

- 3,0 ha community space

- 6,6 ha traffic space

- 10,6 ha green space (2)

Biogeography

The planning area is located on the Munich gravel plain, on the terraces of the Würm glaciation. It is flat and inclined slightly from 514m in the north to 513m in the south. According to the site report by Dragomir, Stahr + Naberland are (1995), natural environment of Ackermannbogen can be summerised:

• Ground

There is no statements about the ground conditions of this city area (such as land-map)because the soils was mostly formed by dumping of strange substances and building materials which are no longer in its natural state.

• Groundwater

The ground in the planning area, as well as the entire Munich gravel plain, is very porous and therefore has significant groundwater resources, including drinking water supply. The depth to the upper aquifer (depth to groundwater) is specified from 8 to 12 m, flowing from south-east to north-west. From the built-over and paved surfaces, the surface water flows through sewerage drains, whilst the river Isar supplies and directs water from the urban area . It is therefore very important to keep in newly developed areas the soil sealing as little as possible.

• Climate

There is low weather exchange from the south and the east due to weak winds, since the planning area is bordered by densely built-up and busy streets. Only the meadows of the Olympic mountain can be seen as the original area of unpolluted cold air. Especially in weak-wind radiation nights, fresh air can flow from the Olympic mountains towards the site center.

A climate-ecological balance function also exerts from the meadows and the richly textured mature trees on the site plan.

• Potential natural vegetation

The potential natural vegetation of oak-horn-beam forests could grow without human influence on the Munich gravel plain. Originally, the gravel layer consisted primarily of oak forests, which were mixed with lime and horn-beam (3).

• Trees

In the planning area, there are valuable trees, which mainly consists of about 60-80 year old sycamore and Norwegian maples and lime trees. The trees have mostly good vigor and a magnificent disposition, most are under the Munich Tree Protection Ordinance (trunk circumference> 80 cm, height> 1m). There is a particularly noticeable band of woodland trees across the barrack area and Saars Road, forming a backbone for path and open space connection.

• Meadows and lawn

The meadows in the planning area consist mainly of relatively thin, ruderal oat-fields, due to lack of care for minor species protection. In some areas of the site there are intensively mowed lawns with little specie features. Also in the area of forest belts no ecologically valuable plants are to be found.

• Habitats

There is a former heliport in the planning area. It consists of a gravel surface on which a dry vegetation has developed over the years, bordered by woodland nursery. In 1981 this area was mapped as a 0.7 ha legitimate habitat. Since then the habitat has expanded twice large.

In the south of the Olympic Park there are poor grassland habitats on former railway land and extensive sand hill areas. Through the narrow neighborhood of the former helipad, there is a floristic and faunal exchange among habitats. The area of the helipad has therefore the ecological value of a stepping-stone habitat.

• Fauna

The birdlife is conspicuously in the planning area, which is mainly due to the old trees with its richly structured tree groups adjacent to Olympic Park. Among others it is possible to spot species of blackbirds, chickadees, spotted woodpeckers, pheasants, ducks and hawks. Rare animals can be found primarily in the area of the former helipad. The animal varies from various ants, butterflies and grasshoppers.

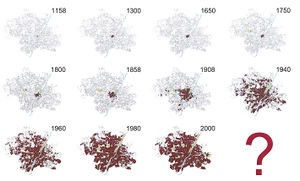

History and dynamics

The barracks in Oberwiesenfeld

The history of the whole area comes from the land named Oberwiesenfeld. Since the late 18th century, city's barracks had been dismissed, or replaced in northwest Munich, the military then focused in Oberwiesenfeld, at that time covered an area which corresponds roughly to the present Dachauer Road in the west, Moosacher Road in the north and Schleißheimer Road in the east. (4)

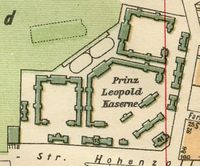

The history of the whole area comes from the land named Oberwiesenfeld. Since the end of the 19th century, Oberwiesenfeld area had been the landing for balloons and airships, both military and civilian. Till 1902 Prince Luitpold established the Prinz Leopold barracks extending from Infanterie Road to Schwere-Reiter Road, which forms today the southern tip of the planning area. By the corner of Schwere-Reiter Road and Winzerer Road are the preserved historical buildings, including the Department of Transportation (Straßenbauamt), the State Archives (Staatsarchiv) and a cafetaria was located.

Adjacent to the planning area to the north of the Dachauer Road was the area of the railway company since 1890, on which the buildings of Munich’s Military Adminstration and Site Management are currently erected, together with the district recruiting office . Since 1896, a new barrack was built in the south of Schwere-Reiter Road, at the corner of Heß Road and an airship department was located, which was later expanded to Luitpold barracks by the Nazis. In 1909, a small condominium for army officials was built in the south of Schwere-Reiter Road, at Barbara Road and still preserved till today. Also under the Nazis time the military had added to existing military building regulations: in 1933, the first part of the "motorcycle-shooters-barracks" (Kraftrad-Schützen-Kaserne) was built in the west of existing Prinz-Leopold barrack. Since 1935 the New-corps barrack errected, today known as Waldmann barrack. Here till the 2nd World War was the accommodation of infantries, pioneers, signal corps and drivers. After the end of the 2nd World War, the planning area was only slightly damaged and some facilities as emergency shelters for refugees and expellees were installed; they also have been used temporarily for commercial purposes.

The barracks were occupied by U.S. forces from 1945 to the late 50s and then claimed against the Federal Army Force. New supplemental buildings were added gradually to the site of the Stetten barracks in 1960s: Auditorium buildings, dorm and gymnasiums. In the same period there was a central heating plant with brick chimney in the middle of the site, to reflect similar architectural style of the whole area. The Waldmann barracks were removed from the grounds for that reason.

The further development of Oberwiesenfeld

After the World War II, in 1951, a 40-meter high pile of rubble from the war’s ruins was dumped in the south of the Nymphenburg Biederstain-canal. This separated the south-eastern part of the Oberwiesenfeld; the spatial connection between this area (nowadays planning area) and the rest of Oberwiesenfeld was lost.

In April 1966, Munich was decided to host the Olympic Summer Games '72. The rubble pile was used as an element in the landscaping concept of the Olympic facilities (5). The Olympic Park was completed in June 1972. Since 1972, the northern (and largest) part of the Oberwiesenfeld was merged into Munich Olympic Park.

The present Ackermannbogen'

Many from different participating groups suggested the planning area of "Waldmann barracks" renamed to "Ackermannbogen" as an advance from the past, from the negative image of the barracks. This proposal was welcomed by citizens and officially used since then. Based on the design of Christian Vogel and Rita Lex Kerfers, an urban contract and development agreement between the property owners and the city of Munich was completed.

In the fall of 2002, the first phase of the construction started from the north-east section. This part was carried on under the "Bavarian Future, a residential funding program of the Free State of Bavaria, as a "model settlement" to try new ways of affordable, environmental and social living in Bavaria. Here approximately 630 households, a mixture of various types of houses and apartments, and a nursery were implemented. Another building on the north end of the large lawn with an integrated cooperative system for children was expected to be ready in spring 2007.

The third phase of construction (north-west section) is the model project which implemented solar local heating system using solar thermal energy. With three large solar roofs it can store energy in the underground reservoir under artificial hills, which is enough to supply approx. 300 housing units. To the end of 2006, 400 apartments, a nursery and an integrated infant daycare were built.

In the south section (second phase), particularly along Schwere-Reiter Road and in the northern part of the Adams-Lehmann Road, next to social housing and public service and high-priced condominiums, a health clinic and a day care center were planned.

In the southwest section (fourth phase), there is a "market square" where the shops and stores are grouped to serve the new district correspondingly. In this area there will be sheltered housing for the arising elderly people. An existing building on the Schwere-Reiter Road was converted into a dormitory. The development plan for the fourth section is still being considered and not decided yet. (6)

Ratio of green/blue and sealed/built-up areas

Green/blue ratio

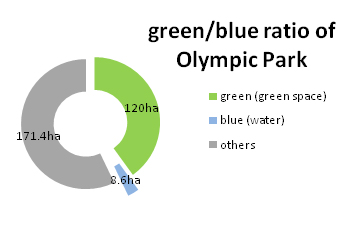

The planning area is primarily within the scope of protection of good water from groundwater. Surface water does not exist. It benefits directly from Olympic Park's Life Sea, or Olympia Lake. This water area covers 8,6 ha and led water from Nymphenburg Biedersteiner channel, which makes a blue/green ratio of approx. 1:14. Within the site itself, this ratio is 0:1 due to no surface water.

The green space aims to cover 30% of the planning area, including 9,2 ha in total, of which 3,3 ha is newly built:

- North hill:

This part takes 1.2 ha green space along the Ackermann Road, modelled like the shape of the Olympic hills on the opposite side and is divided into four areas

• Orchard with local apple varieties (about 8 types of apple trees)

• Sun terrace: The eastern part of the hill is for sun-seeking residents and visitors.

• Calcareous grassland: on the sunny south side of the slope, between the terraces, accommodates current red-list species (e.g the Ida Blue butterfly and partridge)

• Integrated playground: a paved patio area with an integrated playground offering equipments for school children and children with disabilities (including wheelchair users).

- Great meadow: about 1.3 ha, a green axis between Ackermann Road and the high-rise Dawo building runs through the new neighborhood in north-south direction. There are quiet lounge areas, lawns, and opportunities for free playing.

- Deidesheimer yard: located between the Deidesheimer Road and north-east section. The green tree strip hosts several local games. In the south, a chess area is built into the seats. There are also mature trees and benches. The fence is kept to date back to the time of the barracks.

- Sledge hills: The horticulture department asks to keep the sledding hills (under which the solar district heating system is hidden) on the new football field at the Elisabeth-Kohn-Road, but not to use as a sledding hill even in winter, otherwise it will damage the vegetation cover.

- City forest: is considered to be not enough. It is the green zone between Saar Road and the square.

Sealed/unsealed ground ratio

According to the Construction plan with Green structure no. 2010, the sealed area rate is approx. 50%

Cultural/social/political context

Social context

The conversion has started for fifteen years, for that the inhabitants of the first section needed great imagination and pioneering spirit. Although many hopes and wishes were pinned on the emerging new city district, hardly anyone could imagine at first how it might turn out in the future. After the difficult early years when planning deficiencies emerged, such as a lack of schools, the overall concept of the city is now back on track, not least through civic involvement. Various municipal funding measures that awarded grants subsidising home ownership and rents led to the emergence of a new urban district with affordable housing at Ackermannbogen. Young and old, and in particular families who would have been forced out of Munich’s city centre to the periphery on account of the high rents, found a new home in the many new buildings.

There is still evidence of gentrification problems in many parts of Munich, however. There is a general housing shortage in the city on the River Isar, affordable rented housing is generally scarce, especially in the city centre. Admittedly, in view of the growing need, Ackermannbogen with its 2,200 apartments is just a drop in the ocean. But the new district at least shows ways in which cities can counter the trend towards dying city centres and the expansion of urban commuter belts around the city. Planning is now under way for the site’s fourth and final construction phase. At last, the district is also going to get a supermarket. The site’s last southern tip will be lively, that is for sure. Some 40% of the planned apartments are being developed by building cooperatives and community building groups. Such private house-building cooperatives have obvious advantages over profit-orientated property developers. The future inhabitants are already involved at the planning stage, discuss their future district with the city and want to achieve their ambitions with regard to the quality of their homes and their lives. (7)

Population of Munich

- Population growth

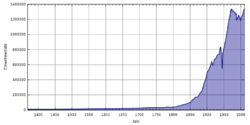

The population of Munich was only 24,000 in 1700, but it doubled every 30 years, and in 1852 the population exceeded 100,000, qualifying it a big city (Großstadt) by German administrative standards. By 1883, Munich had a population of 250,000; this doubled to 500,000 in 1901, making Munich the third largest city in the Deutsches Reich after Berlin and Hamburg. The population is forecast to rise by 7.8% between 2003 and 2020 (96,988 persons). Projected population growth 2003-2020 for Munich (principal residences) (8):

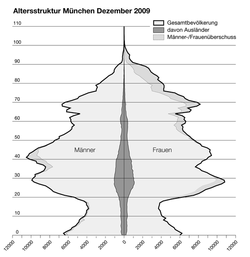

In December 2005, the proportion of foreigners was 23.3% or 300,129 persons in absolute figures. The largest groups of these are Turks (43.309), Croatians (24,866), Serbians (24,439), Greeks (22,486), Austrians (21,411) and Italians (20,847). 37% of foreigners in Munich come from countries within the European Union (9).

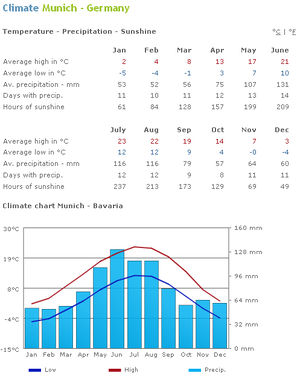

Political context Ackermannbogen is part of two significant model programs of Munich: the "Bavarian Future" and "Solar Local Heating". It is also in the framework of the city's policy for green energy development. In the EUSEW conference in Brussels, on March 29th 2010, the Department of Health and Environment, city of Munich declared its decision towards municipal climate protection: Self-imposed obligation: - 10 % CO2 every 5 years - 50 % CO2 by 2030 - All households in Munich supplied with renewable electric power by 2015 by the public utilities company - All households and commercial customers supplied with renewable electric power by 2025 (11) Local ClimatePresent climate conditionsThe city of Munich is classified in the Köppen classification as Cfb (Oceanic). It is almost directly on the edge of two classifications, however, with the Dfb (Humid Continental Warm Summer Subtype) climate zone just to the east of the city. The warmest month of the year, on average, is July. The coolest month of the year, on average, is January. Showers and thunderstorms bring the highest average monthly precipitation totals in late spring and throughout the summer. June, on average, records the most precipitation of any month. The winter months tend to bring lower precipitation, on average, and February averages the least amount of monthly precipitation for the year. The higher elevation of Munich and the proximity of the Alps play a significant role on the climate, causing the city to have more rain and snow than many other parts of Germany. The Alps affect the city's climate in other ways, as well, including a warm downhill wind from the Alps (föhn wind), which can raise temperatures sharply within a few hours, even in the winter. The location of Munich at the center of Europe dictates that many climatic factors impact the city, making for fluctuating weather conditions more often than in other locations on the continent, particularly compared with areas further west and those south of the Alps. At Munich's official weather station, the highest and lowest temperatures ever measured are 37.1 C˚, on August 13, 2003, and -30.5 C˚, on January 21, 1942. (12) Extreme weather conditions The city of Munich has recently been confronted with flood in 2005 and 2010. Winters are harsh. Expected changing Temperatures in the Bavarian Alps have risen by 2 degrees Celsius over the last 150 years—nearly double the world average—and the south German state of Bavaria says most of its glaciers will disappear over the next few decades as a result. In Bavaria’s first ever glacier report, it found that the total area of the state’s five glaciers has dropped from four square kilometers in 1820 to 0.7 square kilometers today, and that the anticipated warming of the region will cause even more melting. The only glacier that is expected to survive after 30 years is the famous Höllentalferner Glacier, which is protected from sunshine by high cliffs. During a presentation of the report in Munich, Bavarian Environment Minister Marcel Huber announced that Bavaria would spend more than $1.3 billion on climate protection and on Germany's planned nuclear energy phase-out to combat rising temperatures. (13) Analysis of vulnerability

Illustration: Map/diagram/sketches/photos/background notes

Proposals for Climate Change Adaption

— Designing to create an environment that is robust and flexible to climate change, by developing a strong green infrastructure, install green roofs, sustainable urban drainage system (SUDs), planting native species, incorporating recycling systems for waste water.

Green infrastructure represents a holistic approach to the natural and built environment which recognises the important, multifunctional role it has to play in providing benefits for the economy, biodiversity, wider communities and individuals as well as playing an important part in climate change adaptation. Components of green infrastructure can include: — street trees and hedgerows — parks — playgrounds ' A network of spaces and natural elements that are present in and interconnect our landscapes. Green spaces and corridors help to cool our urban environments, improve air quality and ameliorate surface run-off. A green infrastructure planning approach will reduce flood risk, protect building integrity and improve human health and comfort in the face of more intense rainfall and higher temperatures. Well-connected green infrastructure also provides wildlife corridors for species migration in the face of climate change as well as wider benefits for recreation,community development, biodiversity, food provision and place shaping. ' Green roofs, roofs which are covered with vegetation and soil, reduce run-off and subsequently relieve the pressure on drainage systems, particularly at times of high intensity rainfall. Additionally, the benefits afforded to biodiversity are significant by providing wildlife habitats, particularly in urban areas. They also enhance the thermal performance of buildings and have an important role to play in reducing the urban heat island effect. Green roofs also have the potential to contribute to wider landscape character in a particular location. ' Sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDs) reduce the negative impacts of development on surface water drainage. SUDS minimise the risk of flooding and pollution via attenuation and storage with additional benefits including improvements to local environmental quality, the creation of habitats for biodiversity and general improvement to the quality of life for local communities. ' Understanding what species to plant, where to plant them and the conditions different species require in order to thrive a sustainable environment can be created. This knowledge is invaluable in the face of changing climatic conditions, particularly arising from the impacts on the quality and availability of water and the potential increase in pests and disease. ' Incorporating grey water (domestic waste water) recycling systems into the design process can assist in adapting to hotter drier summers when pressure on conventional supplies is likely to be greatest. Grey water can be used in place of these conventional supplies in, for example, irrigation and toilet systems.

There are various aspects of the park which help adapt to climate change. These include: — Local district heating from renewable solar energy. Two hills were built from the material that was removed during construction of the site. One of these, the West Hill, incorporates an innovative and experimental concept in sustainable energy; a 6000m3 hot water tank beneath its surface in which solar energy is stored. This provides 50% of heating energy for the 320 homes of building phase 2. — Sustainable use of resources. Modelling the open space design with approximately 20,000m3 of gravel from the construction of the adjacent buildings. Providing sustainable drainage structures which allow rainwater to seep directly into the ground water through layers containing microbiotic organisms. — Reducing the carbon footprint of individuals. Providing necessary infrastructure within walking or cycling distance. Creating attractive cycling paths and pedestrian ways thus encouraging uptake of sustainable forms of transport. — Creating urban carbon sinks and reducing the urban heat island effect. Using green roofs to cover the water tank and energy control centre. Adding to the total biomass in the town by planting native trees and creating lawns. — Supporting biodiversity. Providing habitats for biodiversity migration. Proposals for Climate Change Mitigation

Through our discussion,we consider that climate change mitigation in our case study area depends not only on the application of solar energy, but also on any possible details of measures on sustainable use of resources, reducing the carbon footprint of individuals, creating urban carbon sinks, reducing the urban heat island effect and supporting biodiversity.

Fundamentally a city is established by inhabitants and infrastructure. The whole production and consumption needs energy to transform, reserve and produce. Therefore, energy theme is first and foremost and long-term question to solve. Only through applying methods as energy-consumption, reduction and self sufficiency, we can achieve sustainable developed areas, while the question of energy is always existing .

'In Ackermannbogen, inhabitants don't need one car, and if you ever do, there is a car-sharing station right in the district. You can live in a leafy green area in the city center, free of exhaust fumes, traffic and noise. This is a model that may turn out to be a blueprint for the future if the inhabitants do their bit. 'Rainwater collection device installed on each building connected to the watering system of the urban green space,at the same time in the direction of the sun construct the plant wall. As much as possible do not waste any little resource, as well as make most use of it. Your scenario

By 2060 Ackermannbogen will turn into a vibrant energy self-sufficient ZEROcarbon city, which is access to balance between energy demand and request. At same time it will create a optimized status among the quantity of inhabitants and houses and the job opportunities.

The future development of climate change in this area will probably emphasize on maximized natural oxygen bar. What's more, according to the biodiversity is totally large increasing, it will become a excellent habitat for animal and vegetation. Furthermore, people live in a harmonious and sustainable environment, not to mention natural disasters. What can be generalized from this case study?

Ecological Evaluation equivalent CO2-emission of solar installation 222 t/a reduction related to condensing boiler system 213 t/a reduction related to conventional district heating 150 t/a

'Public acceptance: This case would need to develop a well communicated strategy to convince stakeholders of the option of 100%. Citizen should feel they are rewarded financially. A zero loan subsidy was suggested as an option for retrofitting households with energy efficiency and renewable measures. 'The financing tools: to take public&private partnerships between the city,banks, energy service companies and households to engaging 'The relationship between with other districts and regions is hardly balance, it will more and more people come Ackermannbogen working, there will be a large number of commuter. But you can not restrict the growth of the urban economy, so it must long-term consider the development city and neighborhood.

This case focuses on seasonal storage of the heat collected with solar panels and was lauched in 2007 after almost 10 years of preparation. This area is a perfect practical example of building a green energy system and an innovative concept of integrating solar heating machines with green space. Presentation Slides

References(1) according to DRAGOMIR report, 1995 (2) Fachexkursion: Stadtentwicklung aktuell - München am 20/6/2005 und 21/6/2005 in München (Institut für Städtebau und Wohnungswesen München der Deutschen Akademie für Städtebau und Landesplanung) (3) according to Carl Troll, 1926 (4) Richard Bauer and Eva Graf, 1986, in "Stadt im Überblick München im Luftbild 1889 - 1935 (5) Gernot Brauer and Dirk Reinartz, 1991, in "Milbertshofen. Ein Portrait aus dem Münchener Norden. Munich off the beaten track von Gernot Brauer und Dirk Reinartz" (6) http://www.ackermannbogen.de/wiki/Geschichte (7) http://www.goethe.de/kue/arc/zds/en6791858.htm (9) Munich Statistical Office (Statistisches Amt der Landeshauptstadt München) (10) Munich Statistical Office (Statistisches Amt der Landeshauptstadt München) (11) Solare Nahwärme und Langezeit-Wärmespeicher (Forschungbericht zum BMU Vorhaben 0329607L. Solites) (12) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munich (13) CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE ALPS. Facts - Impacts - Adaptation (Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety) http://www.zaharias.net/wb-ackwohn.php?lg=en http://www.docstoc.com/docs/46703256/Planning-Implementing-and-Monitoring-of-Large-Solar-Projects http://www.eubia.org/uploads/media/EUSEW_CA-EUBIA_event-_summary.pdf |